Sometimes in yoga class I hear voices in my head. No, I’m not losing my mind – rather, I keep being reminded of lessons I’ve absorbed from my teachers over the years, both the ones I loved and the ones I didn’t. Their “voices” trigger muscle memory, but also something more – a deeply ingrained wisdom.

We’re nearing the end of the traditional school year; my semester of teaching is already over. I often whether my students have taken anything away with them from our short time together. Sometimes I tell them straight out what I hope they will remember: pay attention, don’t lose sight of your strengths, remember to breathe. But once they’re gone from my sphere, what do they recall? Have I given them anything that serves them in their future?

Current pedagogy tells us that teachers talk too much, that if students are really going to learn and internalize concepts, they need to be the ones generating the ideas and doing more of the talking. But it takes a special kind of teacher to pose the right questions, the challenging statements, or even the metaphors that prompt students to think critically and come up with valuable ideas.

When we take the responsibility for our own learning, it doesn’t necessarily matter if what we hear from one teacher contradicts what we were told by another. This happens sometimes in yoga class. One teacher will instruct that the position of the feet be just so for a certain posture; another will say something different. Or one will say the hand should rest just here, another will say no, it shouldn’t. That used to annoy me, now it just makes me smile, because I know I can count on the wisdom of my body to position feet, hands or whatever just where I need them to be. At the same time, I’m still hearing the voices of teachers saying things like “Don’t collapse into the posture,” or “Imagine that your shoulder blades are the temple doors,” and their whispers tell me what adjustments I need to make in that moment.

Most of us talk too much, and listen not nearly enough. What if we were to see ourselves as being both teachers and students, simultaneously? Instead of passively taking in information, students also need to be able share and teach it, but they need tools and the right environment for that shift to happen. Otherwise the wisdom – whether it’s the teacher’s voice or our own — doesn’t stick. My younger sister, who just received her doctorate in education, has mastered the creation of that kind of environment. It doesn’t matter whether she is sitting with a class of sixth graders or with a group of adult learners — she raises everyone up by the respect she shows them and the joy she brings to the process. She perfectly embodies the concept of taking your work very seriously, but not taking yourself too seriously. She is humble enough to know that she has as much to learn from the sixth graders as from her professors.

Last week, my sister shared a reflective practice on her professional blog that came out of a course for educators. The first two questions of it could (and perhaps should) be used by anyone who aspires to be a lifelong learner:

What have you learned this week?

How have you learned this week?

Her point is that to incorporate learning into practice, we need reflection. We have to be able to articulate not only what we learned, but how we learned it. Whether that’s kinetically, through practicing postures in yoga, or through the use of a metaphor, like the temple doors, reflection on the process reinforces learning and stores those voices in memory.

A couple of years ago, I heard from a former student unexpectedly. He wasn’t a particularly stellar student, nor had I been that close to him. It had been at least a year, maybe more, since he was in my class. But he emailed me to say that he was using the breathing techniques that he learned in my class and they were really helping him. I guess he was hearing voices too.

My older sister and I like to tell people how we constructed paths around our room with our collection of Little Golden Books. I have no idea how many books we actually had, but at the time, it seemed liked hundreds. Since they were all the same size, we could line them up and turn them into roads. While we were supposed to be napping, somehow we were developing a sense that we needed to have a path to somewhere else.

My older sister and I like to tell people how we constructed paths around our room with our collection of Little Golden Books. I have no idea how many books we actually had, but at the time, it seemed liked hundreds. Since they were all the same size, we could line them up and turn them into roads. While we were supposed to be napping, somehow we were developing a sense that we needed to have a path to somewhere else.

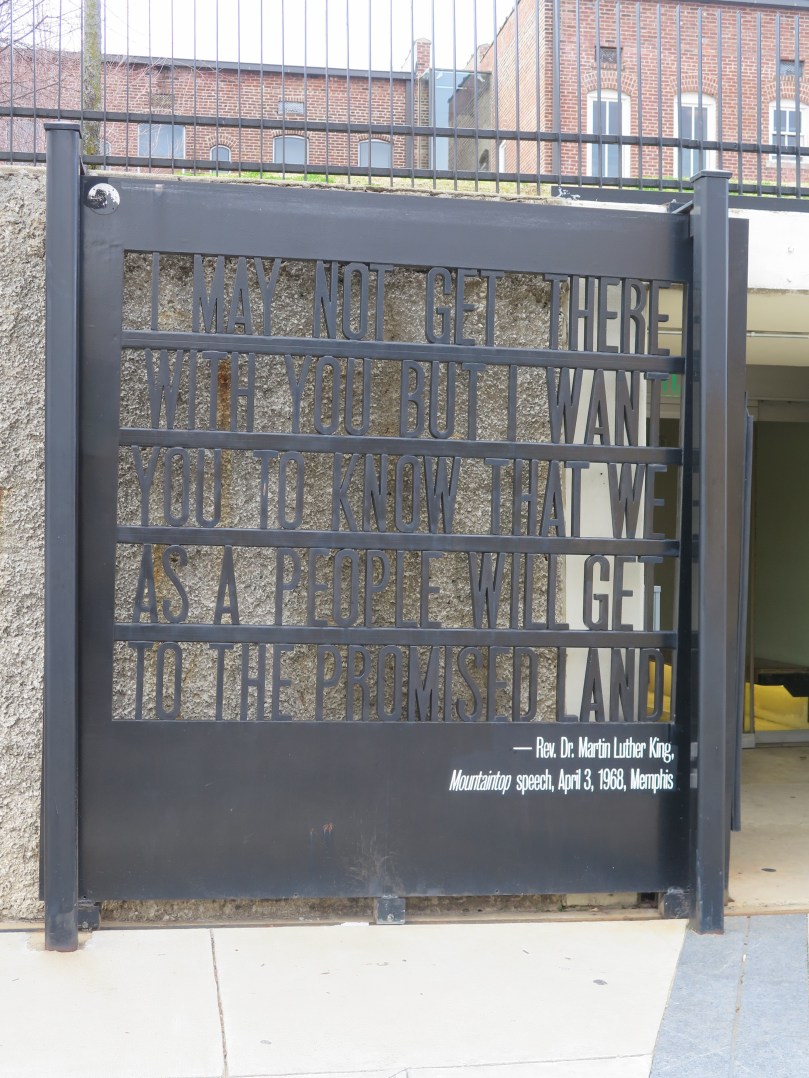

Are you feeling like it might take a miracle to get through the next four years? Do you doubt how much control you have over what happens to you? If so, it might be a good time to take stock of your physical, emotional and psychological “bank account”. What resources do you have and how can you best put them to use?

Are you feeling like it might take a miracle to get through the next four years? Do you doubt how much control you have over what happens to you? If so, it might be a good time to take stock of your physical, emotional and psychological “bank account”. What resources do you have and how can you best put them to use?

The letters are a way for me to know people I never met, or to know the younger selves of people I only knew when they were older. The letters sometimes reflect an optimism that was missing later in their lives. Often the change from optimism to discouragement is recorded in the letters, as with the relative who between the 1830s and 1840s lost 11 of 12 children, divorced his wife, and thought his brother had forgotten him. I’m fascinated by these people, and I wonder if my children and grandchildren might feel the same if they ever come across my old letters and my younger self.

The letters are a way for me to know people I never met, or to know the younger selves of people I only knew when they were older. The letters sometimes reflect an optimism that was missing later in their lives. Often the change from optimism to discouragement is recorded in the letters, as with the relative who between the 1830s and 1840s lost 11 of 12 children, divorced his wife, and thought his brother had forgotten him. I’m fascinated by these people, and I wonder if my children and grandchildren might feel the same if they ever come across my old letters and my younger self. While Seneca has a somewhat mixed historical reputation, he is still considered to be one of the first great Western thinkers, and much of what he had to say about emotions is relevant to us today. When he said that “Contentment is achieved through a simple, unperturbed life,” he was talking not only about emotional regulation, but also gratitude, because contentment is impossible without feeling grateful for what we have already. Contentment requires us to stop asking for things, so that we can reflect on what is present.

While Seneca has a somewhat mixed historical reputation, he is still considered to be one of the first great Western thinkers, and much of what he had to say about emotions is relevant to us today. When he said that “Contentment is achieved through a simple, unperturbed life,” he was talking not only about emotional regulation, but also gratitude, because contentment is impossible without feeling grateful for what we have already. Contentment requires us to stop asking for things, so that we can reflect on what is present.