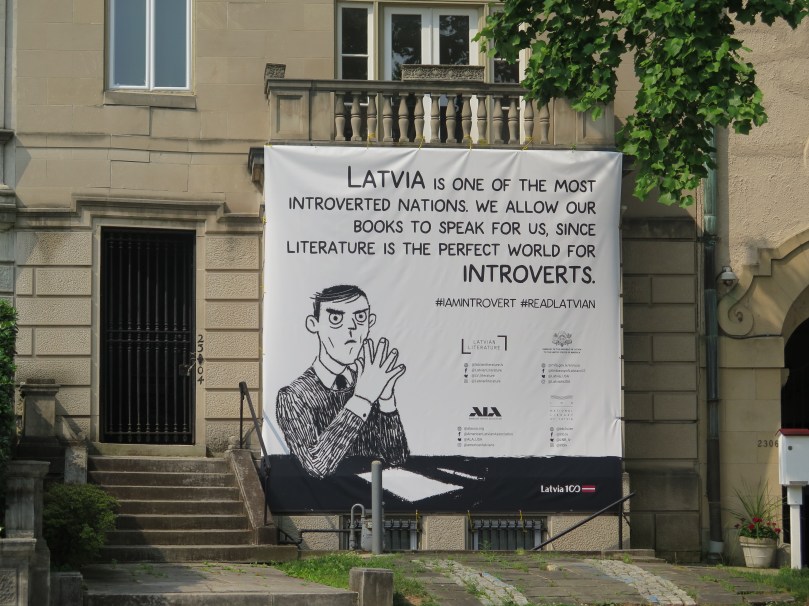

Do your bookshelves contain a story about you as well as the stories within their covers? What could a stranger walking into your home learn about you from the titles she saw there? I asked myself these questions when I came across this banner in front of the Latvian embassy:

Apparently it’s a thing for Latvians to make gentle fun of themselves for being so introverted. But it totally makes sense that a nation of introverts would also be a nation of writers and readers. Introverts, after all, like to have plenty of alone time and prefer to think things through before speaking them out loud. And what better way is there to spend solitary time than with a book or pen?

When I review my bookshelves, I see someone who has some favorite authors (Amy Tan, Chris Bohjalian, Ann Patchett) and nerdy interests (“The Gene,” “Longitude”), but also a healthy supply of the classics, plenty of biographies, and a sizeable collection on stress, spirituality and wellness. There are books for every mood – whether it’s a desire to escape, a curiosity about the world, or a quest for answers about life. Sometimes I deliberately search for a specific book, other times I read whatever is available. But no matter what, I read.

Here’s what I’ve recently been enjoying:

Bridge of Clay by Markus Zusak. This is a beautifully-written novel about love and loss by the author of “The Book Thief.” It’s the story of five brothers living near Sydney, Australia who have to deal with the death of their mother and the abandonment of their father. The story goes back and forth in time so that we get a full picture of each character and what drives them. I was slow to be drawn in, but by half-way through, I couldn’t stop reading. I only wish they wouldn’t categorize this book as “young adult” in my local bookstore, because so many fewer people will find it.

The Extraordinary Life of Rebecca West by Lorna Gibb. I’ve been a fan of Rebecca West’s ever since reading her magnum opus, “Black Lamb and Grey Falcon,” many years ago, before visiting Yugoslavia for the first time. While this biography is not particularly well-written, it is fascinating all the same for its in-depth look at this formidable 20th century British woman. West was ahead of her time, breaking ground as a writer, journalist and literary critic. She was well-known for her coverage of the Nuremberg trials and for her long relationship with H.G. Wells.

November Road by Lou Berney. What if it was the mob who killed JFK? That’s the premise of this novel about a low-level fixer for a New Orleans mobster who has to flee when he realizes he knows too much. When he meets a woman and her children on the road, he uses them as a convenient cover until he realizes that he actually cares for and wants to protect them. Don’t try to guess the ending of this one.

The Summer Before the War by Helen Simonson. This might qualify as “summer reading” if I believed in such a thing, although it would be misleading to characterize this book as “light.” It is a sweet romance about a young woman who comes to teach school in a small English town right before the onset of the first World War. But it doesn’t shy away from the horrors of that war, and it also addresses topics such as sexism, classism and homosexuality in a typically genteel British way.

Louisa May Alcott once said that “Good books, like good friends, are few and chosen; the more select, the more enjoyable.” I suspect that Alcott was an introvert, as am I, but I don’t see the need to be as selective about books as I am about friends. Ranging wide and choosing eclectically can, after all, lead to so many surprising discoveries. I was puzzled a while back when a neighbor asked me what kinds of books I collect (he liked certain types of history). Why would I “collect” just one genre or topic when the whole world is out there?

What do my bookshelves say about me? That I prefer a feast to a single course, a saga to a short story, a journey rather than a day trip. And speaking of trips, if you’re planning one, be sure to grab a book on your way out the door.

This is why the concept of “drishti” is so important in yoga, and can also be a practice that helps us off the mat. Drishti is a Sanskrit word that means “gaze” or “sight”; but also vision or point of view. By practicing drishti, we potentially develop better focus, concentration, and receptivity. It is a technique, but also, Life says, a metaphor.

This is why the concept of “drishti” is so important in yoga, and can also be a practice that helps us off the mat. Drishti is a Sanskrit word that means “gaze” or “sight”; but also vision or point of view. By practicing drishti, we potentially develop better focus, concentration, and receptivity. It is a technique, but also, Life says, a metaphor.

He goes on to say that these knots will grow tighter and stronger if they are not untied, and lead to feelings such as anger, fear or regret, creating “fetters” that effect us, even if they are repressed. They eventually express themselves through “destructive feelings, thoughts, words or behavior.” In other words, rudeness and unkindness are as contagious as a physical illness, and we can become carriers without intending to be. It’s not too much of a leap to see a connection to the recent decline in civility across American life and the erosion of trust among people.

He goes on to say that these knots will grow tighter and stronger if they are not untied, and lead to feelings such as anger, fear or regret, creating “fetters” that effect us, even if they are repressed. They eventually express themselves through “destructive feelings, thoughts, words or behavior.” In other words, rudeness and unkindness are as contagious as a physical illness, and we can become carriers without intending to be. It’s not too much of a leap to see a connection to the recent decline in civility across American life and the erosion of trust among people.

So my overall message was that if they want to be around in 4 years or 8 years to start doing good again, they need to practice self-care right now. Here are some of the things we talked about:

So my overall message was that if they want to be around in 4 years or 8 years to start doing good again, they need to practice self-care right now. Here are some of the things we talked about:

Stress reduction programs and personal choices such as meditation, exercise or disconnecting from email can only alleviate symptoms. The root cause of much workplace stress — corporate culture — is not something that any one individual can change. People are willing to work hard, and even to work long hours, if they see the work as meaningful. In a MIT Sloan Management Review article, Catherine Bailey and Adrian Madden write that meaningfulness is more important to employees than salary, advancement, or even working conditions. Meaning is something that people often discover for themselves. Good leaders can’t make it happen, but research shows that poor leadership can almost certainly destroy it. What makes people feel that the work is meaningless?

Stress reduction programs and personal choices such as meditation, exercise or disconnecting from email can only alleviate symptoms. The root cause of much workplace stress — corporate culture — is not something that any one individual can change. People are willing to work hard, and even to work long hours, if they see the work as meaningful. In a MIT Sloan Management Review article, Catherine Bailey and Adrian Madden write that meaningfulness is more important to employees than salary, advancement, or even working conditions. Meaning is something that people often discover for themselves. Good leaders can’t make it happen, but research shows that poor leadership can almost certainly destroy it. What makes people feel that the work is meaningless?