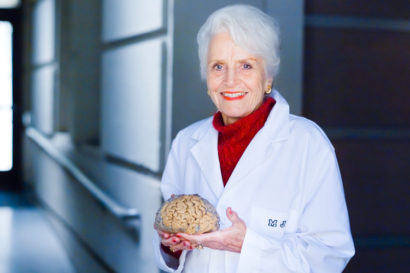

Marian Diamond is best known for studying Einstein’s brain, as well as her penchant for carrying around a hatbox with a human brain inside. But my memories of her revolve around the color-coded lectures she used to give in her anatomy class at U-C Berkeley. Before we had PowerPoint, we had Marian Diamond and her colored chalk.

We would arrive in the lecture hall and find the chalkboard covered with an outline of the day’s class, complete with drawings of anatomical structures. Several different colors of chalk were used to separate parts of the lecture or demonstrate various pathways. I never knew exactly what I would see when I walked in, only that I would be mesmerized for the entire class period by the clarity of her presentation and her dynamic teaching style. Of all the professors I had in college, she is one of only two or three whose classes I vividly remember.

So when I heard that Dr. Diamond died last week, at the age of 90, I was sad for only a moment, and then I smiled, thinking back to that Berkeley lecture hall. Marian Diamond was an expert in brain development, and I realize now that she wasn’t just teaching us about the anatomy of the brain, but actually changing our brains too. She was one of the first scientists to demonstrate neuroplasticity and to test theories of how the right stimulation can promote brain development at any age.

In the introduction to her book, “Magic Trees of the Mind,” Diamond wrote that “The brain, with its complex architecture and limitless potential, is a highly plastic, constantly changing entity that is powerfully shaped by our experiences in childhood and throughout life.” She believed, and showed, that nurture is every bit as important as nature in determining how our lives turn out.

Back when I was in Marian Diamond’s class, I was contemplating a career in nursing, but unprepared for the competitiveness of Cal pre-med students. My laid-back studying habits weren’t a good match for the tough courses I was taking, and I ultimately switched majors. Little did I know that many years later I would go into the field of health education. Now I rely on Diamond’s work all the time in the courses I teach on stress management.

The critical factors in nurturing healthy brain development, according to Marian Diamond, are a healthy diet, physical exercise, being challenged, having new experiences, and being loved – especially love in the form of touch. In studies of rats, she showed that those living in an enriched environment had thicker cerebral cortices, the biggest part of the brain and the one most important for attention, memory and learning. She also learned that rats who were held and petted every day lived longer than others. While much of her work focused on children’s brain development, especially the negative effects of growing up in impoverished environments, she also realized that we retain the capacity for growth throughout life. As she wrote,

“Perhaps the single most valuable piece of information learned from all our studies is that structural differences can be detected in the cerebral cortices of animals exposed at any age to different levels of stimulation in the environment.”

People know this already, even if they don’t know anything about science. A Gallup survey several years ago showed that “learning something new” was one of the biggest predictors for whether someone thinks they had a good day. We’re bored if we’re not challenged, and we languish if we’re not loved. We know we feel better if we eat healthy food, and think better when exercise gets blood flowing to the brain.

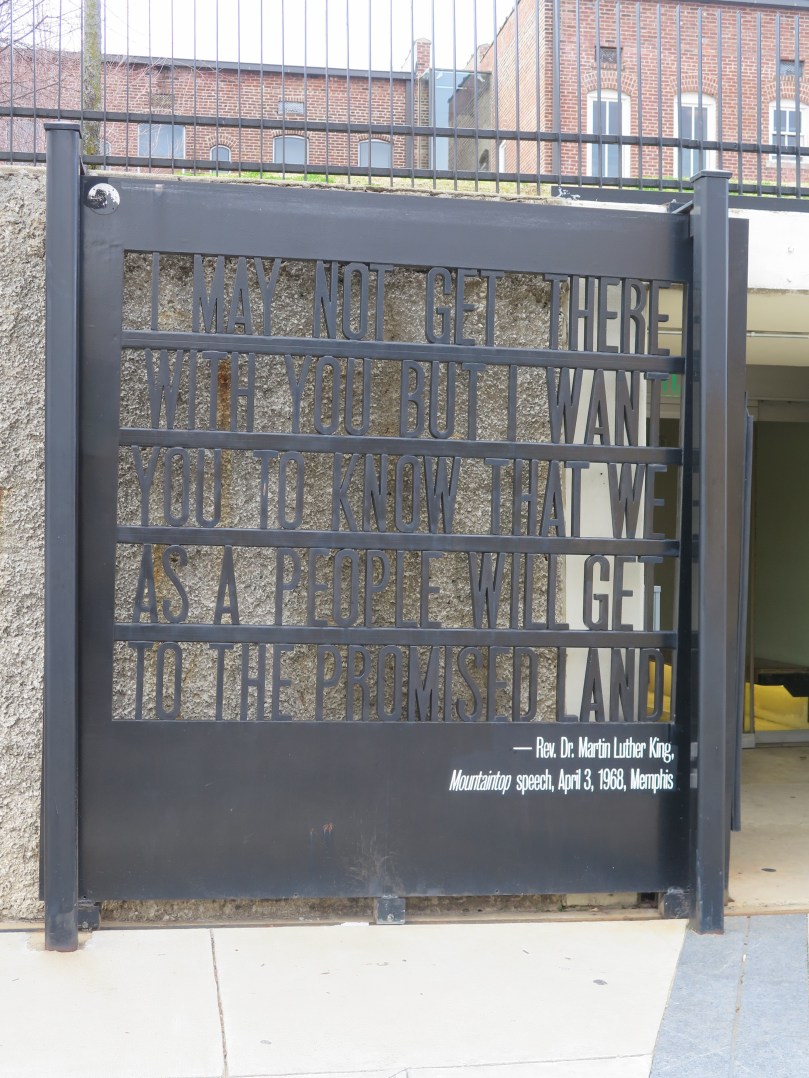

Daniel Defoe wrote that, “The soul is placed in the body like a rough diamond, and must be polished, or the luster of it will never appear.” What we learned from the diamond that was Marian is that the brain needs its own share of polishing and nourishment for us to lead a rich, fulfilling life.

Great Falls Park – the rocky passage of the Potomac down the Mather Gorge, accessible by way of the Olmsted Island bridges, provides a pretty awe-inspiring outing that I never tire of.

Great Falls Park – the rocky passage of the Potomac down the Mather Gorge, accessible by way of the Olmsted Island bridges, provides a pretty awe-inspiring outing that I never tire of. The monuments, while man-made, have a whole lot of grandeur about them.

The monuments, while man-made, have a whole lot of grandeur about them. In America, we can’t compete with the Greeks or Romans on the ancient past, but we do have the advantage of recent history here in Washington:

In America, we can’t compete with the Greeks or Romans on the ancient past, but we do have the advantage of recent history here in Washington: The original columns from the U.S. Capitol can be seen at the National Arboretum. The way they rise up out of nothing, in the middle of a huge expanse of green, is spectacular.

The original columns from the U.S. Capitol can be seen at the National Arboretum. The way they rise up out of nothing, in the middle of a huge expanse of green, is spectacular. In both Ireland and Australia, I took breathtaking drives along coastal roads. That’s tougher to replicate here where we’re inland, but how about the cherry blossoms in spring:

In both Ireland and Australia, I took breathtaking drives along coastal roads. That’s tougher to replicate here where we’re inland, but how about the cherry blossoms in spring:

Are you feeling like it might take a miracle to get through the next four years? Do you doubt how much control you have over what happens to you? If so, it might be a good time to take stock of your physical, emotional and psychological “bank account”. What resources do you have and how can you best put them to use?

Are you feeling like it might take a miracle to get through the next four years? Do you doubt how much control you have over what happens to you? If so, it might be a good time to take stock of your physical, emotional and psychological “bank account”. What resources do you have and how can you best put them to use?