Why can one person walk with ease across a rope strung between two tall buildings, while another wobbles on a beam five times as wide? Why can one person meet life’s challenges with calmness and purpose, while the next person seems buffeted by the slightest turbulence? The difference may well be the quality of equanimity, “mental calmness, composure and evenness of temper, especially in a difficult situation.”

My own recent failures to maintain composure led me to reflect on my capacity for equanimity. I realize that when I am over-tired or surprised, or when dealing with phone or cable companies, I can sometimes completely lose any equanimity I possess. But at least I am noticing when it happens, which I believe is a step toward deepening my ability to stay calm.

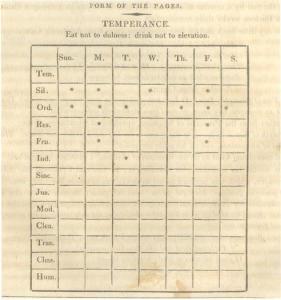

Benjamin Franklin was well-known for developing his character through self-monitoring. He had a checklist of 13 virtues that he considered important, and he evaluated himself every day to see how he had done. His virtues included things like temperance, frugality, sincerity and humility. But number 11 on his list was the virtue of tranquility, which he described as, “be not disturbed by trifles, or at accidents common or unavoidable.” That sounds a lot like equanimity to me.

Buddhist teacher Gil Fronsdal writes that the Pali word “upekkha” can be translated as equanimity. It literally means “to look over”, to become the observer rather than the thinker, to see the big picture. Perhaps the tightrope walker is practicing upekkha when he calmly walks between buildings without a net – is he observing himself from above, visualizing not just himself, but the rope, the buildings, the sky, the earth?

It’s important to realize that maintaining an even temper during difficult times doesn’t mean that someone is apathetic. It is merely the balancing point between suppressing emotions and feelings on the one hand, and overly identifying with them on the other. It’s the sweet spot where you accept that you can’t control the actions of other people, only your own actions and reactions.

Equanimity is considered one of the four great virtues in Buddhism (along with lovingkindness, compassion and the ability to feel joy with others). A study at UCLA on spirituality in higher education concluded that “Equanimity may well be the prototypic defining quality of a spiritual person,” someone who can find meaning in times of hardship and who feels generally at peace with life.

So how do we develop equanimity? Pay attention. Observe what you are experiencing in body, mind and spirit. Engage in self-reflection so that you are more in touch with your thoughts and feelings. Notice when you are reacting rather than responding. Jon Kabat-Zinn suggests that we commit to “meeting each moment mindfully, with as much calmness and acceptance as possible,” and embodying an “openhearted presence” when engaging with others.

So how do we develop equanimity? Pay attention. Observe what you are experiencing in body, mind and spirit. Engage in self-reflection so that you are more in touch with your thoughts and feelings. Notice when you are reacting rather than responding. Jon Kabat-Zinn suggests that we commit to “meeting each moment mindfully, with as much calmness and acceptance as possible,” and embodying an “openhearted presence” when engaging with others.

Bringing more mindfulness to each situation will help you make the subtle shift to being the observer, but it takes practice. You may not always succeed, and sometimes your composure will be shaken, but look back at the end of each day, much like Ben Franklin did, and set an intention for greater equanimity tomorrow.